Memorials serve a sensitive but critical role in society. Memorial architects have a social responsibility to honour the departed in a way that is meaningful to the living.

To accomplish this purpose, I believe architects should strike a balance between aesthetic innovation and upholding the fundamental cultural significance of the tragedy they commemorate.

This is undeniably a challenging task, as shown by the derisive criticism of the UK Holocaust Memorial in London. Some felt the memorial went too far towards the aesthetic, at the cost of functionality. Jewish families who had lost relatives in the Holocaust pronounced that the design ‘evokes neither the Holocaust nor Jewish history.

The Cenotaph exemplifies perhaps a more accepted instance of memorial architecture in London. Edwin Lutyens defied the convention of realist monuments by adopting a simplistic intention. His advance was successful, the memorial experiencing an immensely positive public response; in its inaugural week over 1 million people had flocked to pay their respects. A century later, the Cenotaph remains integral to WW1 remembrance in Britain.

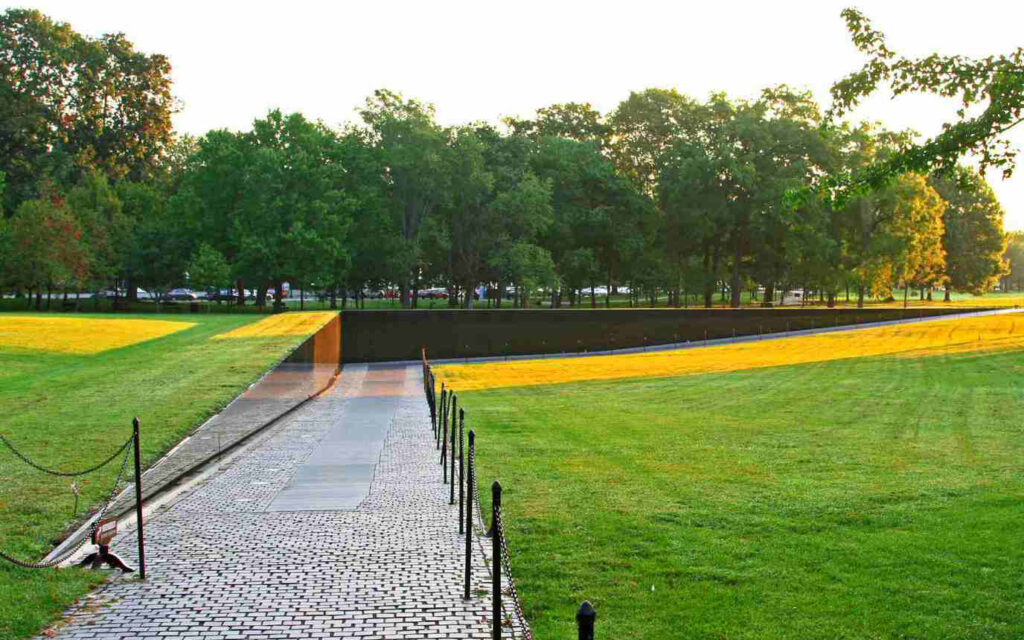

The Vietnam War Memorial in Washington DC also broke tradition. Instead of rising up from the earth, the memorial constitutes two granite walls embedded into the ground. Maya Lin devised this raw scar in the land to be emblematic of the pain caused by the war. It indeed earned controversy, but her memorial remains one of the most notable to date, invoking emotional conversations which help keep alive the memory of those whom it represents.

The National September 11 Memorial in New York is another remarkable example of memorial architecture, featuring two deep pools that lie where the North and South towers obliterated in the 9/11 attacks once stood. These pools exist as a harrowing echo of what once was, their chasmic nature in direct opposition to the vertical protrusion of the towers. I remember peering anxiously over the rim of the pools, watching the water plunge into the void below, and experiencing an apt but overwhelming sense of absence.

It is important to note that the memorial also has taken steps towards being environmentally sustainable, earning recognition as ‘one of the most eco-friendly plazas ever constructed’. The plaza features an irrigation system that collects and stores rainwater, nurturing trees that form a ‘green roof’.

Lastly, I wanted to mention Clifford Pearson’s prevalent proposal. He offers a memorial honouring a present-day crisis, suggesting the reformation of 1100 Pennsylvania Avenue into a ‘COVID-19 Memorial. There is some significance in the repurposing of an old space into a new; it represents the resurgence of a changed society after the implications of the pandemic. It also highlights the necessity of immediately constructing a memorial after the tragedy, in order to maximise its cultural relevancy and impact.

Memorials are therefore so much more than ornamental structures. They embody an essential requirement of society to withstand time and remind future legacies of our past. Given the permanence of memorials it seems important to me that they also nod to environmental sustainability, in light of its pertinence in society today. Perhaps one of the next memorials will pay tribute to those affected by climate change?