The Gateway of India is a national landmark. Built as a mixed-style triumphal arch, it overlooks the Arabian Sea and borders the cosmopolitan city of Mumbai. The effect of the diverse settlers in this city are apparent when examining the array of architectural styles that resides in Bombay, or in the case of the Gateway, a mixture of styles in one monument. The Gateway was designed by Scottsman George Wittet originally for the landing of King George V and Queen Mary for the 1911 Imperial Durbar. In contrast, by the end of British rule over India, the last British ship left in 1948 through the Gateway’s central passageway. The Gateway then represents, I argue, a lasting presence of British colonial influence which confers myriad historical and stylistic implications. By forming a visual comparison between the Gateway and the ancient Arch of Constantine, the ways in which this influence manifests can be understood.

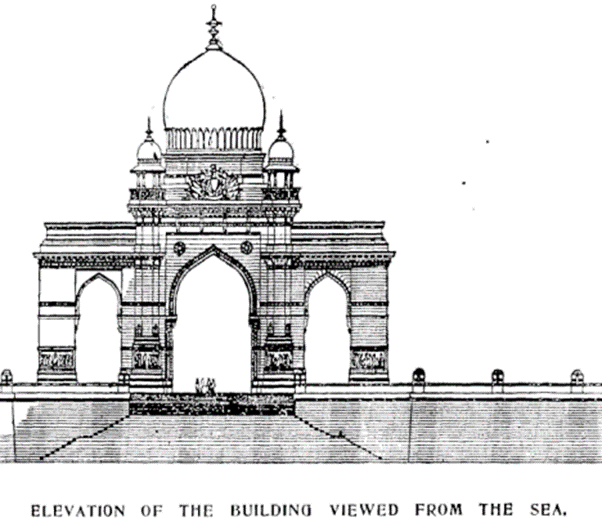

The Gateway of India is a tripartite arch. It stands 85 ft tall with the northwest facade facing the city of Mumbai and the southeast facade facing the sea. These two dominant facades have tripartite passageways through the arches; one length-wise passageway connects the two short facades (southwest/northeast) as well. Visitors see end-to-end through these passageways either out to the sea or into the bustling metropolis of Mumbai. Four turrets rise above the rest of the structure at the corners of the central archway, leading to the top of the monument where the top of the domes are exposed.

Of notable significance is the architect of the structure, George Wittet. Wittet was just one of many “imperial architects” from Britain who erected architecture with colonial and international influences. The import of British architects during the early twentieth century period guided much of the British traditionalist aesthetic. Even when “Indic elements” were incorporated, the interpretation, definition, and degree of Indian heritage was always perceived through the lens of the British colonizers.

It is important to acknowledge that this robust influence of “imperial architects” originally emerged from the ousting of indigenous (and colonial) engineers from high leadership roles. The Indian engineers were made to solve the technical problems. The British architects took the lead on designs. The British ascended to positions of power in many different ways: for instance, by dominating choices in architectural style and promoting the use and craft of British materiality. These modes were inherent to the design and construction of the Gateway of India, and the monument that stands today is inextricably linked to these histories.

Regardless of whether the indigenous or the imperial architect was in power, the principal intention of the monument itself was to celebrate the Imperial Majesties. Inscribed in English on the monument is the following: “Erected to commemorate the landing in India of their Imperial Majesties King George V and Queen Mary on the second of December MCMXI.”

Yet in a news article from 1912 published in the The Times of India, the Government outlined different aspirations to Wittet: “Government have come to no decision as yet in regard to the design.” “They wish the public to have an opportunity of expressing opinions.”

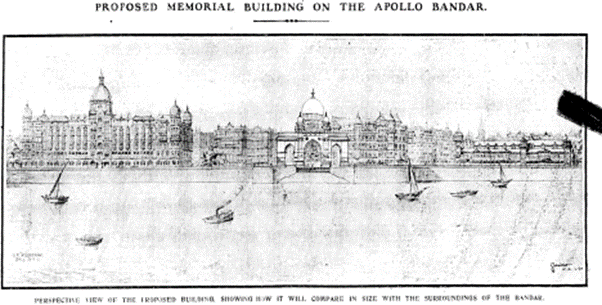

Perspective drawings for The Gateway were published and given prominence so that a large section of the public “may appreciate what is in contemplations” and offer suggestions and criticisms accordingly. A design requirement was that the gateway must be a “building” so as to be able to host future ceremonies in Bandar and not simply be a monumental yet functionless “arch”. The government said that despite the Gateway’s intention to commemorate the entrance of the Imperial Majesties into India, it was the general effect as viewed from the sea that should be chiefly considered. As is not always the case with British colonial architecture, the colonisers wanted the public to be able to have a say in the design. And ultimately, this would lead to the British architects imitating traditional Indian architectures in their design of The Gateway.

Given this, Wittet navigated the design process by combining traditional elements in a non-traditional manner which can be understood through the lens of Classic Roman triumphal arches. At first glance the Gateway follows the general form of the Arch of Constantine – tripartite, main cornice dividing the arched portion from the inscribed attic. However upon closer inspection, pointed arches invoke an Indo-Islamic aesthetic (Indo-Saracenic) as opposed to the semi-circular arches found in Roman counterparts. While the Arch of Constantine has many figural, sculptural elements, the Gateway has none, instead exhibiting floral latticework elements, found along the attic and in the jali screens above the smaller entranceways. Coupled with the square (quadrilateral) geometries of the sections of the Gateway in plan, these details support a Mughal influence. The transmutation of traditional Roman architectural elements to those of Indian origin promotes the Gateway’s “indigeneous”/ Indo-Saracenic aesthetic, while not escaping the Roman tradition altogether.

Ultimately, many colonial influences are incorporated into the history, materiality, form and function of the Gateway of India. Its Roman triumphal arch-form still stands. Its inscription dedicated to the Imperial Majesties still reads. But, the Gateway also represents the British finally leaving India and freedom from those origins. And so the Gateway, both in terms of its function and form, tells the story of two intertwined cultures.