In 1919, a White House-commissioned expedition measured that a trip from the east to west coast took a staggering 62 days. Today, thanks to the Interstate Highway System, the same trip takes just 42 hours. The construction of the Interstate Highway System’s roads was extremely standardized; from the speed limit to road grading to exit ramps, the entirety of the system’s form was designed to aid its function, to facilitate people’s understanding of highway traffic regulations and the ease of travel. As a result of its erection, suburban and rural areas of the United States flourished, thriving under unprecedented levels of connectivity that promoted movement of people, goods, and ideas. However, despite the prosperity it brought to these regions, as the Interstate Highway System was designed with little consideration for urban residents, the system’s construction inflicted devastating ramifications upon those living in America’s cities, most significantly affecting African American communities.

At the 1939 World’s Fair, General Motors unveiled a massive, one acre diorama emphatically dubbed, “Futurama.” Complete with miniature skyscrapers, cars, and trees, this diorama displayed the company’s dream for the nation’s future: an America connected by wide, easily-accessible highways that would criss-cross the country.

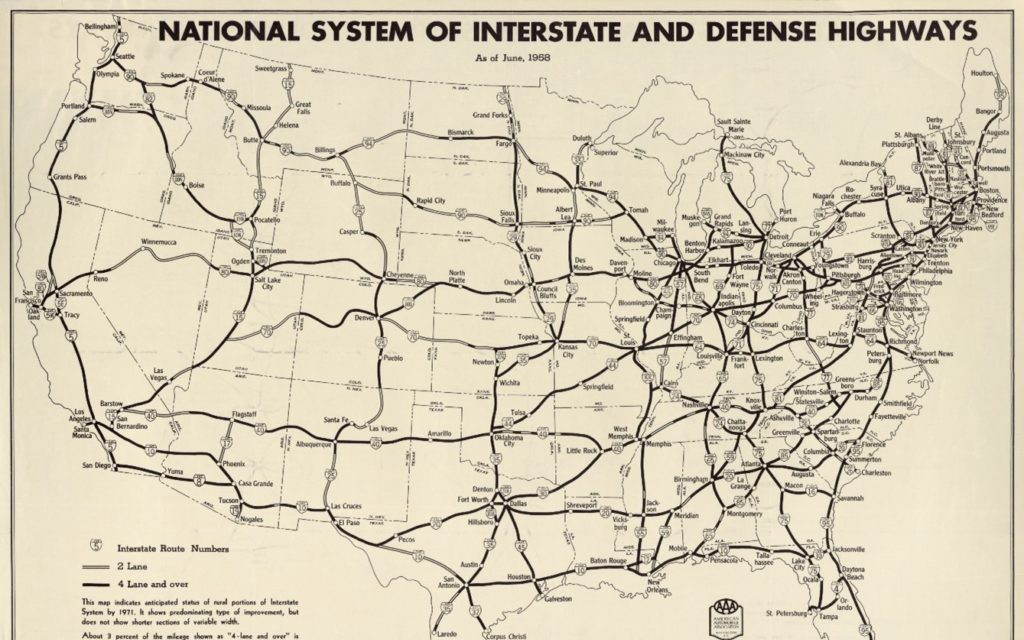

Under the presidential term of Eisenhower, whose military career in Germany had shown him the value of highways, planning of the national system began. The plan’s contributors included a variety of stakeholders: policymakers, automobile interest groups, highway engineers, etc. However, notably, there was a lack of representation for the interests of urban residents.

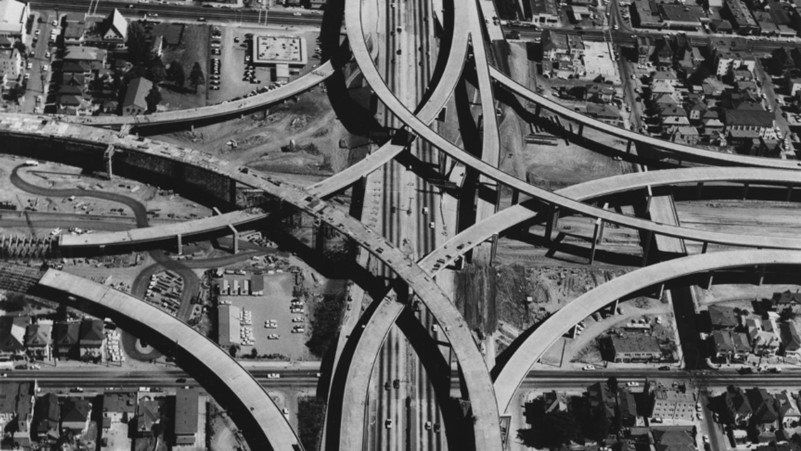

The combination of lack of urban interest representation and commitment to standardized road design meant that highways were poorly adapted to the needs of cities and their inhabitants. In suburban and rural areas, routes could easily be built on underdeveloped or only partially-developed land. However, in cities, these routes resulted in excessive demolition of residences, parks, and other important urban features, especially in low-income neighborhoods, where land was cheap and political opposition was low. This most greatly affected vibrant African American communities, already often forced into disinvested neighborhoods due to redlining, restrictive covenants, and other variations of structural racism. White officials were itching for a reason to get rid of this perceived “blight.” The convenient, paid-for solution? High way construction – more widely known under the guises of “urban renewal”, “slum removal” or other euphemisms.

This phenomenon happened all across the United States, with one of the most prominent examples occurring in Miami. The concentration of Miami’s Black population into a vibrant urban community called Overtown, dubbed as “the Harlem of the South” became part of a resettlement plan ruled by white business leaders to relocate this population demographic to the agricultural fringes. By building the Interstate Highway System’s, the plan could be carried out. Hence locals were moved out, ten thousand homes were overtaken, and black businesses were decimated. Almost no residents were compensated, no relocation program was established, and no homes were built to replace the ones that were destroyed.

Ironically, this abrasive technique often ended up backfiring for cities. Displaced residents had to go somewhere, and with no replacement housing built for the demolished areas, this led to overcrowding of other neighborhoods. Those with the means, namely white people, fled to suburban areas to escape not only rising crime rates, but also noise and air pollution generated by the newly built highways. As the wealthier white residents fled, siphoning money away from the cities’ tax bases, and inadvertently creating highly concentrated areas of poverty, continual poverty further drove crime rates. Hence the cycle of white flight was perpetuated. Cities like New Haven and Syracuse still bear the scars of highway construction, suffering from intense levels of racial segregation and poverty concentration.

As a physical manifestation of segregation, highways were highly detrimental to the urban fabric of many cities. Routes that cut directly through communities created physical and psychological rifts that were hard to cross. Neighborhoods encircled by highways were almost completely isolated from others, restricting economic opportunity and facilitating the creation of new ghettos. Highways inflicted a muzzle upon economic and social interaction across communities, cutting many off from jobs and economic growth centers. Of course, the victims of this disruption were often African American residents.

As transportation infrastructure has returned to the forefront of American policy with Biden’s Build Back Better Plan, it’s more critical than ever to prioritize the considerations of diverse communities. Infrastructure design has the potential to either help people flourish or raze their livelihoods to the ground—as the country looks towards the administration's vision for the future of America, it is yet to be seen if they have learned from the country’s past mistakes.