Dear Grandchild,

(push the "play button above and listen to Arirang at Seongyojang while reading this letter).

I began writing you these letters to hold myself accountable to you and your generation. How would you judge the choices I have made? Have I lived an honourable life? Am I doing enough to make the world a better place for you to live? I thought that you would help me hold the course and take the right path, even when it was not the easier one.

Eight years have passed, and your father who was a baby is now almost ten years old. I have just returned from a trip to our homeland for the first time since the Covid outbreak.

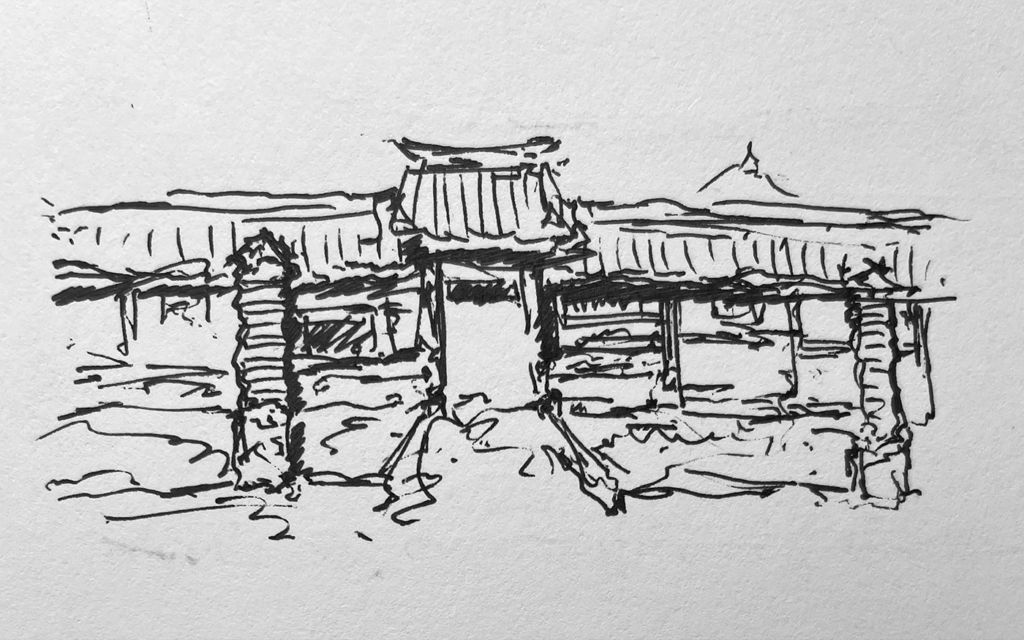

There is a place in the far eastern mountains of Korea called SeonGyoJang. Tucked in a valley, near the DongHae sea, it is the birthplace of my mentor and friend Yi Ki-Ung. I can see it now in my mind’s eye: a perfectly balanced collection of traditional Korean tiled houses, swaying pine trees, and a pavilion hovering over a pond of giant lotus flowers. There it has stood for more than two hundred and fifty years, the home of a single family that has maintained its buildings and the values that they cherish: year after year, generation after generation.

Mr. Yi founded Paju Book City, and like you, he has been my compass and guide on this journey of architecture. With Mr. Yi turning 82 this year, I felt a strong urge to go with him to his birth home. SeonGyoJang is for him an anchor of meaning and a source of strength, and I wanted to experience that with him first hand, while we still have the time.

It was a long and arduous journey for me: an unbroken forty-eight hours from home to Heathrow, through Frankfurt, Inchon, and then a drive east across the whole of Korea.

More than a house, SeonGyoJang is a collection of courtyards, gardens, pavilions, and traditional tile-roofed Hanok. Everything about Mr. Yi: his grace, his dignity, and his thoughtful sensitivity, are mirrored in the architecture of the place. For an architect like me, buildings like this are sacred, embodying the essential ideals of my heritage and culture.

There was a music festival taking place. Ambling up the hill, we were met with the sounds of a string quartet playing in a stone amphitheatre built into the earth, below soaring Korean pines. Arirang, the music I am listening to now: a traditional song about parting, love, and bitterness.

In a bright yellow dress and a wide-brimmed hat, the great-niece of Mr. Yi greeted me in that place. We were the two young ones among the many older family members as we shared food, looked at art, and walked the nearby beach.

In Korea, we say, “eo-reo-shin mo-shi-da.” Younger ones carefully accompany our elders where they wish to go. Mo-shi-da means to accompany with reverence, respect, and patience.

I felt a kinship with this great-niece as we accompanied the elders through conversation and time spent together. In their presence we took care with every word and every movement. There was a reverence going beyond simple politeness or manners. Shoulders slightly bowed, objects held with two hands, and awkward modesty when receiving praise. All these things we shared and communicated, though between us few words were spoken.

I realise as I write that my approach to design and architecture is also like this. I hope to show reverence to our environment, to have dignity in what I design, and to show humility in my responsibility to care for our world and the buildings in which we live.

In SeonGyoJang, one moves from walled courtyard to walled courtyard. In Korean Hanok, gates have a beam at head level, and another beam at the ground level. To walk through these gates one has to bow one's head to pass under the upper beam and take care while stepping over the lower one. The very shape of our architecture encourages us to physically show humility and respectfulness as we use it. How beautiful!

Mr. Yi’s great-niece carries with great dignity the responsibility upholding her family’s tradition and reputation. I also feel that responsibility: the culture and the heritage of our homeland is something to be treasured and cared for. In Korean, I would say “na-ra reul mo-shi da.” I do that, she does that, and those musicians playing Arirang on that sunny afternoon in the eastern mountains of Korea do that as well.

As the words of Arirang say: “Na reul beori-go ga-shineun nim eun ship-ri-do mot ga-seo bal-byeong nan-da.” Who casts me aside and leaves me behind, won’t make it 10 "li" without their feet failing them. *

My grandchild, please remember our culture, please cherish it as I do, and remember that only by living with it from day to day can we keep it alive. Na-ra reul moshi-ja.

With love,

Your grandfather, 25 September 2022

* 3 li is about 1 kilometer. bal-byeong nan-da literally means, foot illness strikes them - this is a very difficult phrase to translate into English - it is a beautifully peculiar Korean phrase.